Propositional Parlor Puzzle

April 21, 2025

I’ve recently been playing Blue Prince, which is a great time if you are a fan of puzzle games like Return of the Obra Dinn or Outer Wilds and also a fan of roguelike games like Slay the Spire.

One of the game’s rooms, the Parlor, features a logic puzzle that is different on each run. In this post we’ll be doing some modelling and analysis of these puzzles. Some people might consider that a spoiler!

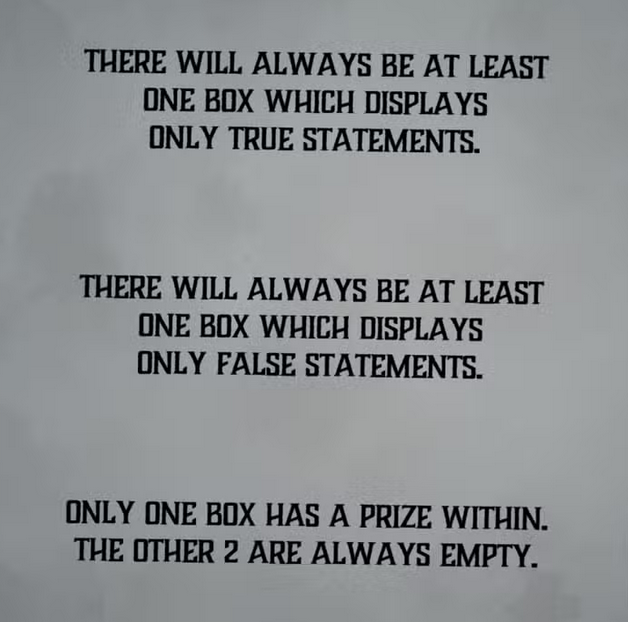

In the parlor, there are three boxes, a blue box, a white box, and a black box. Each box makes some set of statements. We are also given the following rules:

- There will always be at least one box that makes only true statements.

- There will always be at least one box that makes only false statements.

- There is a prize in exactly one box.

Here’s one example of such a puzzle:

Blue: You are in the parlor

White: This box is empty

Black: The blue box is true

The blue box is making an obviously true statement—the box game always takes place in the Parlor. The black box thus is also making a true statement, since blue is true. Since we know by the rules that there must be at least one box making false statements, it can only be white, and so we can deduce that white is not empty and has the prize.

The puzzles get a bit trickier than this sometimes. Consider:

Blue: the gems are in a box with a true statement

White: the gems are in a box with a false statement

Black: The white box is true

There are actually two consistent interpretations here: both

Blue: true

White: false

Black: false

and

Blue: false

White: true

Black: true

are valid. The trick is that the game is not to determine which boxes are telling the truth, but where the prize is, and in this case, either interpretation gives that the prize is in the blue box.

Let’s make a tool that solves these puzzles automatically! This might be useful, if, say, you were making this game and writing a lot of them and wanted some kind of mechanical assurance as part of a test suite that you hadn’t made a mistake.

We can represent these puzzles using propositional logic. This is a kind of logic that is interested in the truth of specific statements. You might think of it as expressions over values only of type bool. We typically have four kinds of objects in propositional logic:

- variables, like

foo,bar, - negations, which take a value and flip its result from true to false or false to true,

- disjuncts, or

ORs over multiple other objects, - conjuncts, or

ANDs over multiple other objects.

We can represent expressions like “it’s cold outside and you should wear a coat” symbolically with variables for ColdOutside and ShouldWearACoat by writing ColdOutside AND ShouldWearACoat. Tough people might not need to wear a coat, so we could write ColdOutside AND (ShouldWearACoat OR IsTough).

Something we are frequently interested in is, given an expression like this:

- is there an assignment of true/false to the variables that makes the expression true, and also

- what are all the assignments of true/false to the variables that make the assignment true?

This problem is called SAT, for “satisfiability.” We’re asking if a given expression is satisfiable. As a simple example, the expression A AND (NOT A) is not satisfiable.

SAT solving is a deep topic and there are many fancy, powerful tools for solving SAT problems. Luckily we don’t need all that machinery, our expressions are going to be simple enough that we can just brute force them, which is good since it’s more fun to just do this stuff yourself.

Let’s start by coming up with a way to represent true, false, and variables (excuse my JavaScript style, I haven’t written it professionally in like ten years):

const True = { type: 'true' };

const False = { type: 'false' };

const Var = name => ({

type: "var",

name,

});

We can use this to come up with all the variables we will need to represent these problems:

const BlueBoxIsTrue = Var("BlueBoxIsTrue");

const WhiteBoxIsTrue = Var("WhiteBoxIsTrue");

const BlackBoxIsTrue = Var("BlackBoxIsTrue");

const BlueBoxIsFalse = Var("BlueBoxIsFalse");

const WhiteBoxIsFalse = Var("WhiteBoxIsFalse");

const BlackBoxIsFalse = Var("BlackBoxIsFalse");

const BlueBoxHasGems = Var("BlueBoxHasGems");

const WhiteBoxHasGems = Var("WhiteBoxHasGems");

const BlackBoxHasGems = Var("BlackBoxHasGems");

We have separate variables for both a box being True and False because a box is not necessarily one or the other if it makes multiple statements: it can have one statement that is true and one that is false, and the box itself is then not “true” or “false.”

Next we need our operators, And, Or, and Not.

const And = (...terms) => {

return {

type: 'and',

terms,

};

};

const Or = (...terms) => {

return {

type: 'or',

terms,

};

};

const Not = term => {

return {

type: 'not',

term,

};

};

Now we can use these to build more complicated expressions that represent the rules in our game.

Remember, at least one box is “true,” and at least one box is “false:”

const OneBoxIsTrue = Or(

BlueBoxIsTrue,

WhiteBoxIsTrue,

BlackBoxIsTrue,

);

const OneBoxIsFalse = Or(

BlueBoxIsFalse,

WhiteBoxIsFalse,

BlackBoxIsFalse,

);

The gems are in exactly one box:

const GemsOnlyInOneBox = Or(

And(

BlueBoxHasGems,

Not(WhiteBoxHasGems),

Not(BlackBoxHasGems),

),

And(

Not(BlueBoxHasGems),

WhiteBoxHasGems,

Not(BlackBoxHasGems),

),

And(

Not(BlueBoxHasGems),

Not(WhiteBoxHasGems),

BlackBoxHasGems,

),

);

We can combine all of these to get the base rules of our game:

const BaseRules = And(

GemsOnlyInOneBox,

OneBoxIsTrue,

OneBoxIsFalse,

);

{

type: 'and',

terms: [

{

type: 'or',

terms: [

{

type: 'and',

terms: [

{ type: 'var', name: 'BlueBoxHasGems' },

{

type: 'not',

term: { type: 'var', name: 'WhiteBoxHasGems' }

},

{

type: 'not',

term: { type: 'var', name: 'BlackBoxHasGems' }

}

]

},

{

type: 'and',

terms: [

{

type: 'not',

term: { type: 'var', name: 'BlueBoxHasGems' }

},

{ type: 'var', name: 'WhiteBoxHasGems' },

{

type: 'not',

term: { type: 'var', name: 'BlackBoxHasGems' }

}

]

},

{

type: 'and',

terms: [

{

type: 'not',

term: { type: 'var', name: 'BlueBoxHasGems' }

},

{

type: 'not',

term: { type: 'var', name: 'WhiteBoxHasGems' }

},

{ type: 'var', name: 'BlackBoxHasGems' }

]

}

]

},

{

type: 'or',

terms: [

{ type: 'var', name: 'BlueBoxIsTrue' },

{ type: 'var', name: 'WhiteBoxIsTrue' },

{ type: 'var', name: 'BlackBoxIsTrue' }

]

},

{

type: 'or',

terms: [

{ type: 'var', name: 'BlueBoxIsFalse' },

{ type: 'var', name: 'WhiteBoxIsFalse' },

{ type: 'var', name: 'BlackBoxIsFalse' }

]

}

]

}

Hm. Kind of ugly. We can write a helper to print these a little more nicely.

((BlueBoxHasGems ∧ ¬WhiteBoxHasGems ∧ ¬BlackBoxHasGems) ∨ (¬BlueBoxHasGems ∧ WhiteBoxHasGems ∧ ¬BlackBoxHasGems) ∨ (¬BlueBoxHasGems ∧ ¬WhiteBoxHasGems ∧ BlackBoxHasG

ems))

∧ (BlueBoxIsTrue ∨ WhiteBoxIsTrue ∨ BlackBoxIsTrue)

∧ (BlueBoxIsFalse ∨ WhiteBoxIsFalse ∨ BlackBoxIsFalse)

Much better! This is using the typical notation of ∧ for AND, ∨ for OR, and ¬ for NOT.

Let’s continue with our rules. We’ll convert a single puzzle into logic for now.

Blue: You are in the parlor

White: This box is empty

Black: The blue box is true

This translates into:

const BlueStatement = True;

const WhiteStatement = Not(WhiteBoxHasGems);

const BlackStatement = BlueBoxIsTrue;

Now we continue with more rules. First, we’ll write a helper. Equiv means two expressions are equivalent, either they must both be true or both be false:

const Equiv = (p, q) => Or(

And(p, q),

And(Not(p), Not(q)),

);

Now, what it means for a box to be “true” is that all of its statements are true, and what it means for a box to be false is that all of its statements are false.

const BlueTruth = And(

Equiv(BlueBoxIsTrue, BlueStatement),

Equiv(BlueBoxIsFalse, Not(BlueStatement)),

);

const WhiteTruth = And(

Equiv(WhiteBoxIsTrue, WhiteStatement),

Equiv(WhiteBoxIsFalse, Not(WhiteStatement)),

);

const BlackTruth = And(

Equiv(BlackBoxIsTrue, BlackStatement),

Equiv(BlackBoxIsFalse, Not(BlackStatement)),

);

const StatementTruths = And(

BlueTruth,

WhiteTruth,

BlackTruth,

);

This implementation assumes that each box only makes one statement, we can fix that later, let’s not worry about it now.

Now our StatementTruths expression looks like this:

(((BlueBoxIsTrue ∧ T) ∨ (¬BlueBoxIsTrue ∧ F)) ∧ ((BlueBoxIsFalse ∧ F) ∨ (¬BlueBoxIsFalse ∧ T)))

∧ (((WhiteBoxIsTrue ∧ ¬WhiteBoxHasGems) ∨ (¬WhiteBoxIsTrue ∧ WhiteBoxHasGems)) ∧ ((WhiteBoxIsFalse ∧ WhiteBoxHasGems) ∨ (¬WhiteBoxIsFalse ∧ ¬WhiteBoxHasGems)))

∧ (((BlackBoxIsTrue ∧ BlueBoxIsTrue) ∨ (¬BlackBoxIsTrue ∧ ¬BlueBoxIsTrue)) ∧ ((BlackBoxIsFalse ∧ ¬BlueBoxIsTrue) ∨ (¬BlackBoxIsFalse ∧ BlueBoxIsTrue)))

Ugh, kind of ugly, actually. Look, we have an expression being ANDed with True. This is fine but it offends me aesthetically. We can simplify that stuff. Let’s make some modifications to our And constructor.

const And = (...terms) => {

// And of zero things is true.

if (terms.length === 0) {

return True;

}

// And of one thing is just that thing.

if (terms.length === 1) {

return terms[0];

}

for (let t of terms) {

// Any explicit Falses make the whole expression False.

if (t.type === 'false') {

return False;

}

// Any explicit Trues can just be excluded, they don't affect the result.

if (t.type === 'true') {

let newTerms = [];

for (let t of terms) {

if (t.type !== 'true') {

newTerms.push(t);

}

}

return And(...newTerms);

}

}

// If any of the terms are Ands already, flatten them.

for (let t of terms) {

if (t.type === 'and') {

let newTerms = [];

for (let t of terms) {

if (t.type === 'and') {

newTerms.push(...t.terms);

} else {

newTerms.push(t);

}

}

return And(...newTerms);

}

}

return {

type: 'and',

terms,

};

};

We can make some similar adjustments to Or and Not. Note we don’t want to go too crazy with the rewrites here, such rewrites can take exponential time. But we’re happy to just clean things up a little bit.

Now StatementTruths looks like this:

BlueBoxIsTrue

∧ ¬BlueBoxIsFalse

∧ ((WhiteBoxIsTrue ∧ ¬WhiteBoxHasGems) ∨ (¬WhiteBoxIsTrue ∧ WhiteBoxHasGems))

∧ ((WhiteBoxIsFalse ∧ WhiteBoxHasGems) ∨ (¬WhiteBoxIsFalse ∧ ¬WhiteBoxHasGems))

∧ ((BlackBoxIsTrue ∧ BlueBoxIsTrue) ∨ (¬BlackBoxIsTrue ∧ ¬BlueBoxIsTrue))

∧ ((BlackBoxIsFalse ∧ ¬BlueBoxIsTrue) ∨ (¬BlackBoxIsFalse ∧ BlueBoxIsTrue))

Much better!

Finally, our final rules are:

const GameRules = And(

BaseRules,

StatementTruths,

);

Which is

((BlueBoxHasGems ∧ ¬WhiteBoxHasGems ∧ ¬BlackBoxHasGems) ∨ (¬BlueBoxHasGems ∧ WhiteBoxHasGems ∧ ¬BlackBoxHasGems) ∨ (¬BlueBoxHasGems ∧ ¬WhiteBoxHasGems ∧ BlackBoxHasG

ems))

∧ (BlueBoxIsTrue ∨ WhiteBoxIsTrue ∨ BlackBoxIsTrue)

∧ (BlueBoxIsFalse ∨ WhiteBoxIsFalse ∨ BlackBoxIsFalse)

∧ BlueBoxIsTrue

∧ ¬BlueBoxIsFalse

∧ ((WhiteBoxIsTrue ∧ ¬WhiteBoxHasGems) ∨ (¬WhiteBoxIsTrue ∧ WhiteBoxHasGems))

∧ ((WhiteBoxIsFalse ∧ WhiteBoxHasGems) ∨ (¬WhiteBoxIsFalse ∧ ¬WhiteBoxHasGems))

∧ ((BlackBoxIsTrue ∧ BlueBoxIsTrue) ∨ (¬BlackBoxIsTrue ∧ ¬BlueBoxIsTrue))

∧ ((BlackBoxIsFalse ∧ ¬BlueBoxIsTrue) ∨ (¬BlackBoxIsFalse ∧ BlueBoxIsTrue))

Now the game boils down to this: find all the satisfying assignments to the variables and figure out what prize location they correspond to. If they all agree on the prize location, the puzzle is valid. If they don’t all agree on the prize location, then the puzzle doesn’t have a unique solution.

Now we need a way to evaluate an expression. We’re going to see a fun consequence of making our constructors self-simplifying in the way we did: we can just walk our tree and replacing variables with their true-or-false-ness, and then let simplification clean everything up. This is kind of weird: the output of eval is another expression, rather than a value, but since we’re giving values to every variable, that expression will always just be a literal true or false:

const Eval = (term, bindings) => {

switch (term.type) {

case 'true':

case 'false':

return term

case 'var':

if (bindings.hasOwnProperty(term.name)) {

if (bindings[term.name]) {

return True;

} else {

return False;

}

} else {

// No assignment given.

return term;

}

case 'and':

return And(

...term.terms.map(x => Eval(x, bindings)),

);

case 'or':

return Or(

...term.terms.map(x => Eval(x, bindings)),

);

case 'not':

return Not(Eval(term.term, bindings));

default:

throw new Error(`can't eval ${term.type}`);

}

}

const a = Var("a");

const b = Var("b");

console.log(

Write(Eval(And(a, b), {})),

Write(Eval(And(a, b), {a: true})),

Write(Eval(And(a, b), {b: true})),

Write(Eval(And(a, b), {a: true, b: true})),

Write(Eval(And(a, b), {b: false})),

)

This outputs:

(a ∧ b) -> no variable assignments were given.

b -> `a` was true, so it got eliminated.

a -> `b` was true, so it got eliminated.

T -> both were true, so the whole expression simplified to True

F -> `b` was false, so the whole expression simplified to False.

Now we can write a little helper to enumerate the (exponentially many) assignments to a set of variables:

function *assignments(...variables) {

let totalCount = 1<<variables.length;

for (let i = 0; i < totalCount; i++) {

let result = {};

for (let j = 0; j < variables.length; j++) {

result[variables[j].name] = (i & (1<<j)) !== 0;

}

yield result;

}

}

Let’s try it:

console.log([...assignments(Var("a"), Var("b"))]);

This enumerates every possible assignment to a and b:

[

{ a: false, b: false },

{ a: true, b: false },

{ a: false, b: true },

{ a: true, b: true }

]

Now we can find all the assignments that satisfy our puzzle:

for (let binding of assignments(

BlueBoxIsTrue,

WhiteBoxIsTrue,

BlackBoxIsTrue,

BlueBoxIsFalse,

WhiteBoxIsFalse,

BlackBoxIsFalse,

BlueBoxHasGems,

WhiteBoxHasGems,

BlackBoxHasGems,

)) {

let result = Eval(GameRules, binding);

if (result.type === 'true') {

console.log(binding);

}

}

which has exactly one output:

{

BlueBoxIsTrue: true,

WhiteBoxIsTrue: false,

BlackBoxIsTrue: true,

BlueBoxIsFalse: false,

WhiteBoxIsFalse: true,

BlackBoxIsFalse: false,

BlueBoxHasGems: false,

WhiteBoxHasGems: true,

BlackBoxHasGems: false

}

Which indeed corresponds to the white box having the gems!

Let’s try our example with multiple interpretations:

Blue: the gems are in a box with a true statement

White: the gems are in a box with a false statement

Black: The white box is true

This is easy to translate into logic:

const BlueStatement = Or(

And(BlueBoxIsTrue, BlueBoxHasGems),

And(WhiteBoxIsTrue, WhiteBoxHasGems),

And(BlackBoxIsTrue, BlackBoxHasGems),

);

const WhiteStatement = Or(

And(BlueBoxIsFalse, BlueBoxHasGems),

And(WhiteBoxIsFalse, WhiteBoxHasGems),

And(BlackBoxIsFalse, BlackBoxHasGems),

);

const BlackStatement = WhiteBoxIsTrue;

Now there are two satisfying assignments:

{

BlueBoxIsTrue: false,

WhiteBoxIsTrue: true,

BlackBoxIsTrue: true,

BlueBoxIsFalse: true,

WhiteBoxIsFalse: false,

BlackBoxIsFalse: false,

BlueBoxHasGems: true,

WhiteBoxHasGems: false,

BlackBoxHasGems: false

}

{

BlueBoxIsTrue: true,

WhiteBoxIsTrue: false,

BlackBoxIsTrue: false,

BlueBoxIsFalse: false,

WhiteBoxIsFalse: true,

BlackBoxIsFalse: true,

BlueBoxHasGems: true,

WhiteBoxHasGems: false,

BlackBoxHasGems: false

}

But as we’d hoped, in both of them the blue box has the gems.

We can close the loop here and automate this process:

let gemBoxes = new Set();

for (let binding of assignments(

BlueBoxIsTrue,

WhiteBoxIsTrue,

BlackBoxIsTrue,

BlueBoxIsFalse,

WhiteBoxIsFalse,

BlackBoxIsFalse,

BlueBoxHasGems,

WhiteBoxHasGems,

BlackBoxHasGems,

)) {

let result = Eval(GameRules, binding);

if (result.type === 'true') {

if (binding.BlueBoxHasGems) {

gemBoxes.add('blue');

}

if (binding.WhiteBoxHasGems) {

gemBoxes.add('white');

}

if (binding.BlackBoxHasGems) {

gemBoxes.add('black');

}

}

}

if (gemBoxes.size === 0) {

console.log("FAIL: no valid assignments");

} else if (gemBoxes.size === 1) {

console.log(`gems are in ${[...gemBoxes][0]} box`);

} else if (gemBoxes.size === 2) {

console.log("FAIL: multiple valid assignment");

}

And that’s that! That solves the bottom half of the problem, which is actually solving the puzzles once the english text is translated into logic. Next week we will tackle the top half.

If you want to mess around with the code in this post it exists in some form here.