Biohacking Implants: When Human Optimization Becomes Too Risky

Key takeaways:

- Biohacking has gone mainstream: What began with fitness trackers and sleep apps now includes hardware implants, with 67% of Americans in a recent survey identifying as biohackers.

- Grinder biohacking goes beyond tracking: Grinders implant magnets, NFC and RFID chips, and other devices directly into their bodies to enhance human capabilities.

- Human augmentation has real risks: DIY implants often happen outside medical settings, which increases the risk of infection, device failure, and even introduces cybersecurity threats.

- The line between innovation and harm remains unclear: There aren’t any clear rules for where enhancement should stop and where safety regulators and safety standards should step in.

A healthy diet and good sleep hygiene are enough to be the best version of ourselves, right?

According to hard biohackers, also known as grinders, the actual way to become your best self is to implant technology under your skin. These are the people who take biohacking further. Think hardware upgrade, not unlike a better RAM or GPU for your PC.

And when we say literally, we mean it. People are implanting hardware such as magnets under their fingertips to sense electromagnetic fields, NFC and RFID chips to open doors or for digital authentication, and even subdermal LED lights.

The point? To enhance human capabilities and merge technology with biology.

Depending on the opinion you’ll form as you read, the most extreme form of biohacking could be revolutionary. Or it could be causing more harm than good.

Is wellness enough anymore, or is human biology an OS waiting to be updated and upgraded?

Let’s unpack both sides of the argument to separate hype from reality and, more importantly, understand the risks.

From Sleep Trackers To Skin Implants: How Biohacking Got Here

Before magnets in fingertips and chips in hands entered the conversation, biohacking looked pretty straightforward.

The first commercial pedometer designed for fitness was the Manpo-kei, developed in 1965, but it wasn’t anywhere near the movement we’re seeing today.

Biohacking started around the early 2000s, when technology began to make it easy for everyday people to measure their own bodies.

Fitness trackers, smartphone apps, and smartwatches created a new kind of feedback loop. You could see things like how long you slept, how many steps you took, and how your heart rate behaved throughout the day.

People used this data to change their behavior based on what their bodies told them.

In 2007, Gary Wolf and Kevin Kelly popularized the term ‘Quantified Self.’

The idea was that by tracking your own data, you could better understand your habits and make informed decisions to improve them.

Tracking tools made nutrition, fitness, sleep, and productivity measurable and fixable.

Biohacking emerged naturally from this mindset. If data could help you optimize things, then why not use it proactively?

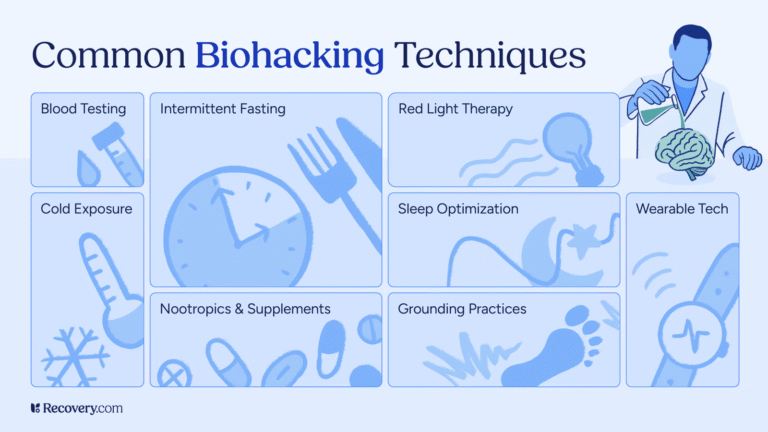

Early biohackers focused on low-risk, lifestyle-based trends. People experimented with methods like intermittent fasting, cold exposure, red light therapy, and sleep optimization.

Doing all this promised incremental improvements rather than a radical transformation. Most of these improvements didn’t need surgery, implants, or any physical enhancements.

Wearable technology was behind most of this experimentation. Fitness trackers and smartwatches gamified health and fitness metrics. Some critics argue that they were designed this way simply to get more people to buy them.

Co-Editor for the Everyday Lifestyle Series, Laura Engel, says that ‘we might have good reasons to be cautious about using gamified fitness apps.’

Over the years, these wearables have gotten great at measuring sleep quality and metabolic markers, but they have also created a narrow focus on what being healthier actually means, versus a more holistic understanding of a healthy mind and body.

Regardless of where you stand on the wearables argument, biohackers made the practice more accessible, measurable, and mostly safe.

Then, some people decided data wasn’t enough.

We’ll get into what we mean by this later, but just to give you some idea of how far people have pushed things, people like Josiah Zayner, a former NASA biochemist, have publicly injected themselves with DIY CRISPR-related materials in self-experimentation stunts to alter their genetics. We weren’t joking about the extremes here.

Biohacking Is No Longer Niche

Time has now passed, and biohacking is more mainstream. Surveys show how far this trend has evolved from early adopters and tech enthusiasts.

According to the 2025 survey mentioned above, more than 1K people, 67% of Americans identify as biohackers, clearly showcasing that this is no longer a niche, but rather a standard, almost expected behavior.

Self-identification varies by definition, but the general definition of a biohacker is anyone who actively tries to optimize their body using data, tools, or structured interventions.

But what if you just want to improve your health by not drinking coffee before bed, getting seven to eight hours of good sleep, and getting enough sunlight each day? Does that make you a biohacker? It depends if you want to identify with the trend or not.

There’s definitely a middle ground between doing your best to stay healthy, popularized by podcasters and health professionals like Andrew Huberman and Peter Attia, and people taking drastic steps to optimize their bodies, like plasma transfusions and stem cell therapy. On his guests podcasts, as well as Humberman Lab releases, Andrew Huberman often advocates for the intricate connection between mental states and physical health.

94% of people believe optimizing their body’s performance counts as a healthy pursuit. This isn’t breaking news: Regular physical activity cuts heart disease risk by about 50%, and healthy habits delay disability onset by roughly five years.

In 2025 alone, 64% of people said they tried a new biohacking method in the same survey we mentioned before.

That could mean changing your diet, experimenting with supplements, or adopting new recovery techniques. Whatever the method, the trend points to a growing confidence in self-experimentation.

People also spend real money on this. Americans now spend an average of $214 per month on biohacking, and in the survey, 82% said the expense feels worth it. That kind of sustained spending shows us they perceive real benefits.

The Three Types Of Biohacking

Biohacking has three different forms. While they all share the common idea of self-improvement, the methods behind them and the risks involved vary a lot.

Nutrigenomics: Rewriting the Menu

Nutrigenomics focuses on how nutrition interacts with your genetic makeup. Basically, practitioners analyze genetic data to understand how their bodies process certain nutrients, fats, or carbohydrates. Then, they adjust their diets based on this information.

Even though this includes the use of cutting-edge tools, this type of biohacking stays true to traditional health practices, and it usually doesn’t involve physical risk. Nutritionists and healthcare professionals typically guide this type of biohacking.

An example of this would be how a mid-30s nurse was treated with nutrigenomics-guided adjustments when doctors integrated her genetics with her symptoms of fatigue and chronic infections, emphasizing precision nutrition.

So, there isn’t much to worry about aside from data privacy and the quality of interpretations.

DIY Biology: Science Outside the Lab

DIY Biology, often called DIYBio, is a bit more rebellious. Participants conduct biological experiments outside traditional laboratories.

They believe that science should be accessible to everyone, not locked behind academic institutions or corporate funding.

For example, at Genspace, a community lab in New York, non-traditional scientists do genetic engineering experiments outside academic labs. Participants include both hobbyists and self-taught biohacks, and they extract DNA from strawberries using household items to build organisms and even create glowing bacteria.

This space is funded by memberships rather than institutional grants and showcases the rebellious ethos by democratizing biotech tools and bypassing academic gatekeepers.

Grinder Biohacking: When the Body Becomes Hardware

Now, let’s get into the nitty-gritty of why we sat down to share all this with you: Grinder biohacking.

Grinder biohacking takes self-optimization to an extreme. Grinders apply hacker thinking directly to their bodies. Instead of wearing technology, they implant it.

Transhumanist philosophies heavily influence this approach, since many transhumanists argue that aging is a disease that technology can slow down or eliminate.

Grinding is all about pushing boundaries, and practitioners believe that technology and science should belong to everyone, and they see the human body as just another platform they can upgrade.

Let’s look at an example: Fecal transplants. Some biohackers are using the literal stool of someone considered healthy and transplanting it into their own bodies to improve their gut health. You can’t tell me this is pleasant or fun, but biohackers do all of this for the purpose of enhancement.

Tim Story was diagnosed with stage 4 small bowel cancer and was given months to live after failed cancer treatments. He received stool infusions that completely shifted his gut microbiome. He had a strong response, including three remissions lasting over a year.

What Makes Grinder Biohacking Different

Enhancing the human body with technology is nothing new. Pacemakers to regulate hearts and hearing aids to restore hearing have been around for years.

There’s also always been the myth that we can extend our lifespan if we do certain things.

The difference lies in the intent and oversight.

Medical implants exist to treat diseases or disabilities, and they fall under strict regulatory frameworks. Grinder implants exist to enhance capabilities, often without medical supervision.

Many of the procedures we’ll describe soon take place in non-surgical environments with no standardized safety protocols.

This is the distinction that defines the grinder movement.

Grinders don’t wait for regulatory approval from authorities like the FDA or for the results of clinical trials. They experiment first and deal with the consequences later.

This mindset certainly fuels innovation, but it’s also a serious risk.

Inside the World of Human Augmentation

We’ve done some digging to serve up examples that explain why grinder biohacking both fascinates and unsettles people at the same time.

Sensing The Invisible With Magnets

Some grinders implant magnets into their fingertips to sense electromagnetic fields. The result feels like a new sense.

Rich Lee, a grinder in the US, has implanted more than seven pieces of technology under his skin.

His fingertip magnets allow him to feel electromagnetic activity in ways most people can’t even perceive. He has described the sensation as discovering a hidden layer of reality.

‘You can feel it because all those nerves in your fingertips have grown around the magnet,” he told ABC News. ‘It has a texture, and you’re feeling this otherwise invisible world.’

Rich Lee also implanted magnets in his ears, which he says allow him to hear through walls. He later added a biotherm chip in his forearm to monitor his body temperature.

But not all of his grinding experiments have ended well. He once implanted shin guards under his skin. A severe infection and terrible swelling led him to remove them himself at home with nothing more than a set of pliers, a procedure that left him with bad scarring.

NFC And RFID Chips Under The Skin

Radio frequency identification (RFID) and near field communication (NFC) chips have become some of the most common grinder implants. These chips come encased in glass and sit just beneath the skin.

Once grinders implant them, these chips can interact with smartphones, computers, and scanners. Grinders use them to unlock phones, open doors, authenticate identity, and even make contactless payments.

Chase Pipkin, for example, uses an NFC chip to unlock his car door and turn on the lights in his home. So, instead of keys or apps, his hand becomes the interface.

These chips don’t need batteries. They only activate when a compatible device scans them. That design makes them relatively simple, and you don’t really have to maintain them at all.

For some users, the appeal is simple: fewer keys, cards, and logins.

The Workplace Chips

A tech firm called Three Square Market offered its employees the option to implant a chip under their skin. It allowed door access, computer sign-ins, and snack purchases with the wave of a hand.

50 of the firm’s 80 employees agreed to the implant.

The same company has announced plans to develop more advanced implantable chips. Future versions could function as GPS devices or store medical history and passport information.

These GPS chips technically wouldn’t be a huge leap from tracking via work-issued phones or a company car, but what about your personal privacy?

What if you were being tracked going to Planned Parenthood? Or an addiction specialist? How about a domestic violence shelter or a place of worship? Companies and institutions could track this highly personal data. Imagine the field day institutions and advertisers could have with this.

Project Blueprint

Billionaire and Kernel’s CEO, Bryan Johnson, invested over $500M in experiments and technology in 2025 to reverse aging and ‘become the most optimized human on earth,’ IDN Financials reports.

According to IDN Financials, he spends over $2M per year on Project Blueprint, where he reportedly uses daily MRI scans, an extreme diet, and even plasma transfusions to optimize his body. Biological markers now reportedly show him as 10 years younger than his actual age.

When Biohacking Solves Real-World Problems

Not all grinder biohacking is based on novelty or convenience. Some uses actually address real-world challenges in creative ways.

Medical Data Where It Matters

Winter Mraz, who has several implants in her body, uses technology to manage a serious autoimmune condition.

She has a lot of allergies, far too many to fit on a medical alert bracelet. So, she stores detailed medical information in an implant.

The chip contains data on her allergies, medications she can’t take, and the type of EpiPen she uses.

Hearing Color Through Bone

Some people are using devices that translate color into sound, known as bone-conducting implants. These devices allow color-blind people to ‘hear’ color through vibrations in the skull.

The technology doesn’t restore natural color vision, but it creates a new sensory pathway. People with the implant can associate specific sounds with colors.

Cameras, Compasses, and New Senses

Some grinder implants add entirely new forms of perception.

Rob Spence, a filmmaker with one eye, uses a prosthetic eye that contains a wireless video camera.

The device includes a circuit board and a battery, and records everything he sees. While it doesn’t transmit vision directly to his brain, it does allow him to document the world from his perspective.

Liviu Babitz implanted an electronic compass in his chest. The device includes a Bluetooth connection and vibrates whenever he faces north.

‘You walk on the street staring at your phone,’ he told the BBC. ‘You want to get somewhere, but you have no idea what’s happened in the world around you because all you did was stare at the screen on the way.’

Neuralink And The Corporate Face Of Human Augmentation

While grinders often operate independently, corporate players have also entered the space, and with far more resources.

Elon Musk’s company Neuralink develops brain-computer interfaces designed to merge humans with AI. He has argued that humans risk becoming obsolete without direct integration with AI.

In his words, humans could turn into “house pets” if AI surpasses human intelligence.

In 2024, the company implanted a device into a person named Noland Arbaugh. The implant allowed him to control a computer cursor and play games using his brain.

Clinical implants are built with security protocols, but that doesn’t make their security impenetrable. New devices get hacked all the time.

Where Biohacking Crosses The Line

Many grinder implant procedures take place outside clinical settings. Practitioners often lack medical training, and sterile environments and standardized health protocols usually don’t apply.

That really introduces the potential for danger.

Implants can migrate, break, or trigger immune responses. Infection is also a constant risk. Some materials may degrade over time or interact unpredictably with tissue. This means you’re certainly giving up a lot to be a grinder.

Research into the long-term effects of this technology is also limited. Scientists don’t really know how these materials will behave in the body over decades, and without oversight, grinders often become their own test subjects.

What Happens If Implants Get Hacked?

Implanted technologies present cybersecurity risks that traditional medical devices don’t.

Chips store data, and if someone gains unauthorized access to this, they could steal personal information or medical records.

While most passive RFID or NFC implants have range and power, biometrics are assumed, so data and authentication still matter. Something as innocuous as a handshake or sitting next to someone at a cinema could cause a data leak.

In potentially extreme cases, compromised implants could even lose functionality or behave unpredictably.

Brain-computer interfaces raise especially serious concerns. Any system that interacts with neural signals needs a lot of protection.

Regulation Hasn’t Caught Up

Grinder biohacking happens mostly outside of regulatory frameworks. Medical device regulations focus on clinical treatments and not voluntary enhancements.

That means grinders don’t have standardized safety guidelines, and governments now have to scramble to decide how much oversight there should be.

On the other hand, overregulation could get in the way of innovation. But underregulation could result in a lot of harm.

Is Biohacking Going Too Far?

That question depends on your perspective.

Grinder biohacking could be the possible next step in human evolution. You could argue that this experimentation drives progress and that early adopters in any setting always face risk.

From the opposite perspective, there are dangers and ethical blind spots. Medical and privacy risks exist, and having technology implanted in your body that could be hacked presents a new challenge for innovators.

Either way, I’m pretty sure biohacking won’t slow down. Implants will become easier to place and harder to detect because technology is getting better and the grinder community is growing, despite cautionary examples. The line between medical necessity and enhancement is likely to become even more blurred soon.

Click to expand list of references:

- https://medicalfuturist.com/the-evolution-of-fitness-tracking

- https://www.quanthub.com/what-is-the-quantified-self-movement/

- https://recovery.com/resources/biohacking/

- https://blog.apaonline.org/2023/02/06/reflections-on-the-gamification-of-fitness/

- https://sanctuarywellnessinstitute.com/blog/biohacking-statistics-trends/

- https://www.verywellhealth.com/lifestyle-factors-health-longevity-prevent-death-1132391

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/216307#google_vignette

- https://www.swintegrativemedicine.com/blog/case-study-for-nutrigenomics

- https://thebiologist.rsb.org.uk/biologist-features/the-unlikely-labs

- https://www.nbcnews.com/health/cancer/cancer-treatment-gut-microbiome-transplant-success-rcna193721

- https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-02-23/biohackers-transhumanists-grinders-on-living-forever/8292790

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hbNpsmOVGt0

- https://www.cnet.com/culture/surgically-implanted-headphones-are-literally-in-ear/

- https://www.freethink.com/series/biohackers/biohacking

- https://www.cnbc.com/2017/08/11/three-square-market-ceo-explains-its-employee-microchip-implant.html

- https://www.idnfinancials.com/news/56222/bryan-johnson-spends-us500-million-to-fight-ageing#

- https://medical-technology.nridigital.com/medical_technology_jan20/from_grinders_to_biohackers_where_medical_technology_meets_body_modification

- https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202112/1242987.shtml

- https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-46442519

- https://www.sciencealert.com/elon-musk-says-we-re-going-to-need-brain-implants-to-compete-with-ai

- https://www.lhtehk.com/technology/how-investing-in-dependend-increasing-to-business/

- https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-49004004

Cassy is a tech and Saas writer with over a decade of writing and editing experience spanning newsrooms, in-house teams, and agencies. After completing her postgraduate education in journalism and media studies, she started her career in print journalism and then transitioned into digital copywriting for all platforms. Read more

She has a deep interest in the AI ecosystem and how this technology is shaping the way we create and consume content, as well as how consumers use new innovations to improve their well-being. Read less

The Tech Report editorial policy is centered on providing helpful, accurate content that offers real value to our readers. We only work with experienced writers who have specific knowledge in the topics they cover, including latest developments in technology, software, hardware, and more. Our editorial policy ensures that each topic is researched and curated by our in-house editors. We maintain rigorous journalistic standards, and every article is 100% written by real authors.