Microsoft’s new 10,000-year data storage medium: glass

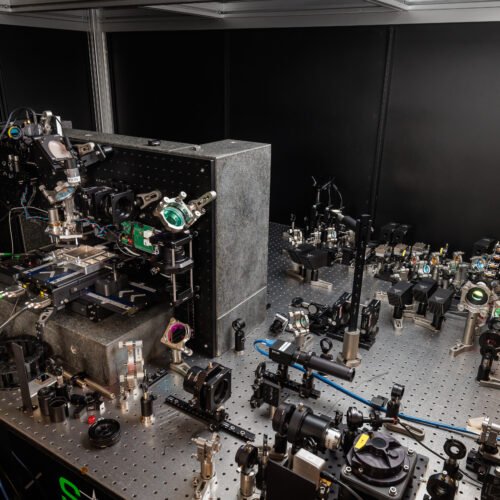

Femtosecond lasers etch data into a very stable medium.

Right now, Silica hardware isn’t quite ready for commercialization.

Credit:

Microsoft Research

Archival storage poses lots of challenges. We want media that is extremely dense and stable for centuries or more, and, ideally, doesn’t consume any energy when not being accessed. Lots of ideas have floated around—even DNA has been considered—but one of the simplest is to etch data into glass. Many forms of glass are very physically and chemically stable, and it’s relatively easy to etch things into it.

There’s been a lot of preliminary work demonstrating different aspects of a glass-based storage system. But in Wednesday’s issue of Nature, Microsoft Research announced Project Silica, a working demonstration of a system that can read and write data into small slabs of glass with a density of over a Gigabit per cubic millimeter.

Writing on glass

We tend to think of glass as fragile, prone to shattering, and capable of flowing downward over centuries, although the last claim is a myth. Glass is a category of material, and a variety of chemicals can form glasses. With the right starting chemical, it’s possible to make a glass that is, as the researchers put it, “thermally and chemically stable and is resistant to moisture ingress, temperature fluctuations and electromagnetic interference.” While it would still need to be handled in a way to minimize damage, glass provides the sort of stability we’d want for long-term storage.

Putting data into glass is as simple as etching it. But that’s been one of the challenges, as etching is typically a slow process. However, the development of femtosecond lasers—lasers that emit pulses that only last 10-15 seconds and can emit millions of them per second—can significantly cut down write times and allow etching to be focused on a very small area, increasing potential data density.

To read the data back, there are several options. We’ve already had great success using lasers to read data from optical disks, albeit slowly. But anything that can pick up the small features etched into the glass could conceivably work.

With the above considerations in mind, everything was in place on a theoretical level for Project Silica. The big question is how to put them together into a functional system. Microsoft decided that, just to be cautious, it would answer that question twice.

A real-world system

The difference between these two answers comes down to how an individual unit of data (called a voxel) is written to the glass. One type of voxel they tried was based on birefringence, where refraction of photons depends on their polarization. It’s possible to etch voxels into glass to create birefringence using polarized laser light, producing features smaller than the diffraction limit. In practice, this involved using one laser pulse to create an oval-shaped void, followed by a second, polarized pulse to induce birefringence. The identity of a voxel is based on the orientation of the oval; since we can resolve multiple orientations, it’s possible to save more than one bit in each voxel.

The alternative approach involves changing the magnitude of refractive effects by varying the amount of energy in the laser pulse. Again, it’s possible to discern more than two states in these voxels, allowing multiple data bits to be stored in each voxel.

The map data from Microsoft Flight Simulator etched onto the Silica storage medium.

Credit:

Microsoft Research

The map data from Microsoft Flight Simulator etched onto the Silica storage medium.

Credit:

Microsoft Research

Reading these in Silica involves using a microscope that can pick up differences in refractive index. (For microscopy geeks, this is a way of saying “they used phase contrast microscopy.”) The microscopy sets the limits on how many layers of voxels can be placed in a single piece of glass. During etching, the layers were separated by enough distance so only a single layer would be in the microscope’s plane of focus at a time. The etching process also incorporates symbols that allow the automated microscope system to position the lens above specific points on the glass. From there, the system slowly changes its focal plane, moving through the stack and capturing images that include different layers of voxels.

To interpret these microscope images, Microsoft used a convolutional neural network that combines data from images that are both in and near the plane of focus for a given layer of voxels. This is effective because the influence of nearby voxels changes how a given voxel appears in a subtle way that the AI system can pick up on if given enough training data.

The final piece of the puzzle is data encoding. The Silica system takes the raw bitstream of the data it’s storing and adds error correction using a low-density parity-check code (the same error correction used in 5G networks). Neighboring bits are then combined to create symbols that take advantage of the voxels’ ability to store more than one bit. Once a stream of symbols is made, it’s ready to be written to glass.

Performance

Writing remains a bottleneck in the system, so Microsoft developed hardware that can write a single glass slab with four lasers simultaneously without generating too much heat. That is enough to enable writing at 66 megabits per second, and the team behind the work thinks that it would be possible to add up to a dozen additional lasers. That may be needed, given that it’s possible to store up to 4.84TB in a single slab of glass (the slabs are 12 cm x 12 cm and 0.2 cm thick). That works out to be over 150 hours to fully write a slab.

The “up to” aspect of the storage system has to do with the density of data that’s possible with the two different ways of writing data. The method that relies on birefringence requires more optical hardware and only works in high-quality glasses, but can squeeze more voxels into the same volume, and so has a considerably higher data density. The alternative approach can only put a bit over two terabytes into the same slab of glass, but can be done with simpler hardware and can work on any sort of transparent material.

Borosilicate glass offers extreme stability; Microsoft’s accelerated aging experiments suggest the data would be stable for over 10,000 years at room temperature. That led Microsoft to declare, “Our results demonstrate that Silica could become the archival storage solution for the digital age.”

That may be overselling it just a bit. The Square Kilometer Array telescope, for example, is expected to need to archive 700 petabytes of data each year. That would mean over 140,000 glass slabs would be needed to store the data from this one telescope. Even assuming that the write speed could be boosted by adding significantly more lasers, you’d need over 600 Silica machines operating in parallel to keep up. And the Square Kilometer Array is far from the only project generating enormous amounts of data.

That said, there are some features that make Silica a great match for this sort of thing, most notably the complete absence of energy needed to preserve the data, and the fact that it can be retrieved rapidly if needed (a sharp contrast to the days needed to retrieve information from DNA, for example). Plus, I’m admittedly drawn to a system with a storage medium that looks like something right out of science fiction.

Nature, 2026. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-10042-w (About DOIs).

John is Ars Technica’s science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots.